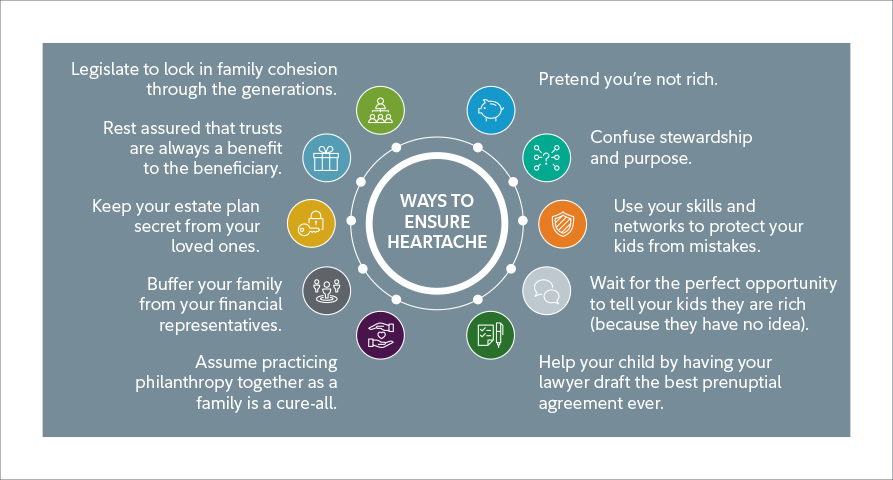

Top ten ways to avoid heartache in your family

Source: Feature article from our U.S. partners

Fidelity is fortunate to serve as a resource for the wealthiest families on issues that go beyond investments and the core of our custody work. At times, we are called upon to help families take advantage of opportunities that their wealth provides, such as defining a long-term vision for social impact or preparing the next generation to take leadership roles in the family enterprise. Other times, unfortunately, we are asked to help address problems that weigh heavily on the family. These problems can result from a single bad action or from decades of unhealthy behaviours. They are rarely caused by malice or intentional ill will; more often, we see bad outcomes emerge from the best of intentions. Why? Unfortunately, many families don’t have the big-picture view to see how small, seemingly rational choices can lead to disappointment, damaged relationships, lack of fulfillment or any number of negative outcomes that leave family members with aching hearts.

For families dealing with heartache, we can bring our ecosystem of third-party experts, thought leaders and consultants to bear on the work needed to help turn the ship around toward happiness and fulfillment. To be sure, this work is hard and not always successful. A better approach is to avoid the heartache in the first place. To that end, we have examined common problems wealthy families face and have traced them back to their root assumptions or decisions. Any one of these issues has the potential to produce heartache in your family. Following the best practices outlined here can go a long way in helping your family down a different path toward happiness and harmony.

Top ten ways to avoid heartache in your family

Unfortunately, bad outcomes can come from seemingly well-intentioned decisions. But, empowered with the experiences of others, families can work to avoid potential missteps.

Avoid pretending you’re not rich.

Many families, especially those who are new to extreme wealth, believe that they will avoid the potential pitfalls engendered by wealth by denying they are wealthy or by hiding from their wealth. This assumption seems logical on the surface, and for those who take pride in their working- or middle-class upbringing, even admirable.

But this attitude can deny the happiness and opportunities that wealth can afford, and potentially lead to extremely negative outcomes. Financial prudence and frugality – points of pride for many wealth creators – an quickly escalate to unhealthy and unnecessary penny-pinching. The urge to hide wealth and the subsequent fear that others are out to discover and exploit that wealth can lead to distrust, isolation and an inability to form healthy relationships. And when wealth is not acknowledged, productive conversations to help children navigate wealth will not happen. For example, consider an investment professional who hit his stride in his 40s and is now worth several hundred million. This wealth clashes with his and his wife’s working- class upbringing and stands in stark contrast to the current financial realities of their extended families. It’s not hard to imagine the challenges the couple might face as others learn about their wealth. The extreme effort they put into keeping their wealth a secret from their friends, family and even their own children could be setting them up for heartache. Their children lack the technical or emotional skills they will need to manage such wealth, and because the wealth is a secret, they cannot begin the process of acquiring those skills.

In this scenario, imagine one daughter is poised to walk away from her dream of being a teacher because she cannot make the finances work. We’re not saying it’s the parents’ obligation to use their wealth to support her career choice, but try to imagine the emotional impact on, and potential damage to, the daughter’s relationship with her parents when she finds out that she abandoned a meaningful life path for tens of thousands of dollars when her parents were planning to leave her millions. Might that change the nature of her relationship with her parents forever? How might her spouse feel?

And perhaps the fear of exposing their wealth is even beginning to create cracks in the couple’s relationship. The wealth creator’s spouse won’t allow him to fly private to a hard-to-reach board meeting, for example, leaving him feeling that she is denying him access to the wealth he made so many sacrifices to earn. The reality here is that just as extreme wealth isn’t the solution to every problem, it’s also not the cause of every problem. Rather than pretending the wealth doesn’t exist, families should consider heeding the advice of James Grubman, PhD, who explored these ideas in Strangers in Paradise: How Families Adapt to Wealth across Generations. Grubman’s research shows that families with the best outcomes reject the binary perspective of “only good” or “only bad” and appreciate the complexity of the situation – one that requires continual reflection and decision-making about what they want to hold on to and what they are willing to let go. Rather than relying on a preconceived notion of wealth to make decisions, these families reflect on their values and aspirations, and then use this as a guide for their decisions. In the absence of absolute rules, they find themselves talking through more situations, both as couples and with their children, and the latter can then begin the process of making sense of and preparing for the complexity they will one day own. Knowing that “right” answers are hard to come by, the parents naturally become more flexible, allowing them to build healthy relationships with their kids.

Avoid confusing stewardship and purpose.

When wealth holders are asked, “What is the purpose of your wealth?” a long, awkward silence usually ensues, followed eventually by a tentative, “Stewardship: it’s my job to be a good steward of this wealth.”

Unfortunately, stewardship is not a purpose; rather, it’s a defensive strategy that keeps wealth in play while doing nothing to clarify why that wealth should be kept in play. Stewardship, as important as it is to many families, often does more to define failure than it does success.

To figure out the purpose of a family’s wealth, the family needs to identify and clearly articulate their life aspirations. Do they want to continue to innovate and create financial wealth? Do they want to produce family members who are the best version of themselves? Do they want the freedom to pursue dreams and passions? Do they want to ease the suffering of others?

After one of our client families articulated that the most important use of its wealth was to help each family member realize his or her full potential, the family completely reprioritized the role of their family office. Having historically only spent on investment professionals and tax attorneys to grow and pass financial assets through the generations, the family realigned the office and invested in education, coaches, mentoring and seed capital to help develop and launch the rising generation.

We worked closely with another family who was intentional and strategic about the family’s purpose from the outset, and completely up front with their daughter about the wealth she would ultimately inherit. “It didn’t really change a thing for me,” she said about learning the exact size of the family’s fortune. “In fact, I think it actually made me want to work harder.” Many families are fearful that if they share too much too soon with their children, they may raise spoiled kids who lack drive and ambition. This particular family used a strategy of ever-present communication to bring about the positive effect they sought. The purpose of the family’s wealth was articulated and lived day in and day out while the child was growing up: to allow her family to continue living a comfortable life while working tirelessly to serve others. To that end, the daughter pursued her master’s degree in public health and today works full time to protect women’s reproductive health rights across Latin and South America, continuing a legacy that was purposefully set forth by her family.

A clear purpose can also release a family from the questions or guilt surrounding how they leverage their wealth. The burden of a billion-dollar inheritance weighed heavy on one wealth creator’s son. Was it his obligation to dedicate his life to protecting and growing the wealth? Would his father disapprove of any career choice that did not also reflect a serious intent to earn? Fortunately, the father and son worked together to explore the intent of the inheritance and the meaning of the money. Wealth creation was a by-product of the father’s decision to follow his passion; it was never his end goal.

Accordingly, the father did not expect his son to dedicate his life to creating great wealth, if that wasn’t what drove his son. To the father, the purpose of this wealth was to give his son the freedom to do what he himself had done many years before: pursue a direction that was deeply meaningful to him. The final outcome: the less-than- common billionaire sixth-grade math teacher. Confusing stewardship with a proactive purpose that can ensure happiness and fulfillment in your family is like buying a map that shows you where you don’t want to go, rather than your ideal destination. If you don’t know your destination, how can you expect to get there?

Avoid using your skills and networks to protect your kids from mistakes.

The urge to protect our children from hardship and mishaps is universal, regardless of affluence. Parents with extreme wealth regularly swoop in to protect their kids from making mistakes and to clean up messes when mistakes are made. Wealthy families have the financial resources to make problems go away (“We have the money to fix this, why wouldn’t we?”), and they often have a strong incentive to do so (“Our family’s reputation would be damaged by word of a drunk driving accident. People will suspect a crash if his car is suddenly gone. We need to replace it right away with something better!”).

We also see a unique dynamic with parents who are wealth creators: Many have been successful because they are smart, strong, self-confident figures who have trusted their instincts and been richly rewarded for doing so. Their business success and accumulation of wealth is proof of the quality of their decisions. With such a great track record, why would they sit back and watch a child make a bad decision? But unintended consequences often come from the best intentions.

We recently connected a consultant with a family to help salvage a relationship between the 90-year-old patriarch and his grand- and great-grandchildren. Why? Because he was a brilliant entrepreneur who always viewed his daughter’s decision- making ability as inferior to his. Objectively, he may have been right, but by inserting himself into every decision when she was young, he stripped her of her confidence and the opportunity to learn from her own mistakes. As a result, she was never able to develop the skills or self-confidence that come from mastery. The daughter, now 70, had struggled all her life with poor and unhealthy decision-making arising from that low self-esteem. She resents her father and is actively pushing a negative narrative about him to her children and grandchildren.

The reality is that children who are never allowed to make their own decisions become adults who are unable to make them. Decision-making is a muscle that needs to be strengthened, and the ability to make good decisions takes years of practice.

Parents who ultimately want to raise adults capable of good decision-making need to empower and support their kids – but this means allowing them to fail. That process of trial and error strengthens their decision-making ability. Requiring them to dig themselves out of their own holes builds resilience, a key component in becoming a healthy inheritor, according to Coventry Edwards-Pitt, author of the book Raised Healthy, Wealthy, & Wise: Lessons from Successful and Grounded Inheritors on How They Got That Way.

Avoid waiting for the perfect opportunity to tell your kids they are rich (because they have no idea).

Many parents we speak with are more terrified about “the money talk” than “the sex talk.” Not only can talking about money be taboo in our society, parents are fearful that if their kids know they are rich, their drive and motivation to live a productive life will vanish. Many parents convince themselves their kids don’t know the family is wealthy. “My kids have no idea we’re wealthy,” stated a client adamantly. We asked, “Didn’t we just spend the past 20 minutes talking about your jet?” Even if your kids don’t know the actual numbers, they have a good idea that you are rich (and they know how to search online). What they don’t know is what being rich means: How should they act? What is expected of them? What is the money for? How should they relate to others?

These questions are where the heartache is grounded. If you are not helping your kids make sense of what it means to be wealthy, somebody else will – maybe even a reality television star. Young people are bombarded by money messages that may not align with your family’s values, and these messages from social and mass media put them at risk of developing a distorted sense of self tied to money. They could develop a negative emotional connection to money, and view it as something to be feared, hated or embarrassed by.

Furthermore, parents who don’t talk to their children about wealth deny them time to prepare the technical and emotional skills needed to handle the extreme wealth they will ultimately (or in tragic situations, instantly) be responsible for. Dr. Timothy Habbershon, managing director at Fidelity Investments and head of Family Thought Leadership and Practice, is quick to point out that more than 70% of lottery winners end up in bankruptcy. Why? Because most lottery winners have no experience with extreme wealth, and find themselves without the technical or emotional skills for soundly spending, saving and giving money. “Don’t make your kid a lottery winner,” Dr. Habbershon is fond of saying.

To avoid this heartache, accept that it’s not “a talk” about wealth. It’s about creating a culture of being able to talk about wealth, including talking early and often. Encourage a lifetime of dialogue. Build comfort with money and wealth as a topic with kids from a young age, so they feel safe coming to you to help them make sense of it. Don’t preach or lecture. Not sure where to start? Not sure what they are ready for? Simply ask them about their thoughts or questions. Listen. Repeat.

And while there are nuts-and-bolts technical literacy skills they will need to have (such as how to save, spend responsibly, create a budget, etc.), don’t confuse those technical skills with the sense-making that needs to happen around wealth. Sense-making should be driven by your values and beliefs, by your ideas about what it means to be rich, and by what you believe the purpose and obligations of your wealth to be.

Avoid asking your lawyer to draft the best prenuptial agreement ever for your child.

This is not an opinion on whether prenuptial agreements should or should not be used. We are saying, however, that we’ve seen too many relationships damaged because of how a prenuptial was presented to the newly engaged.

Picture your newly engaged child and their partner, in love, all smiles, excited about building a life together. Now picture a lawyer who is being paid to absolutize the interests of another family while sliding a complex legal document across the table to your child and telling him or her they are expected to comply. Will that gesture be received as a warm and loving welcome? As a message of acceptance and trust? Or is it more likely to be received as, “Even if we love you, we don’t trust you, and you don’t have a voice”?

Relationships – between families and even couples – can be altered in a heartbeat. The risk grows greater when those getting married are financially unequal. Even for couples who understand and accept the rational reasons for prenups, the initial emotional response may taint the relationship for years.

Avoiding heartache doesn’t mean avoiding prenups. As Keith Whitaker, PhD, outlines in his Prenuptial Agreements: A Practical Guide for Families, there are a number of procedural steps that can be used to help reduce the risk to relationships.

When possible, set the expectation at an early age that your family uses prenups, before there is a specific significant other in the picture. Doing so will avoid prenups being misconstrued as an indicator of dislike or distrust of the fiancé(e).

After the engagement, when it comes time to open the discussion, start from a place of love. Explain why you think considering a prenup could be beneficial to the couple and to the families. If you can’t start the conversation with the right tone, try harder. Don’t use fear and mistrust as your foundation.

Even better, you could co-create a prenup with the couple. Ask them to reflect on what they want out of a marriage and what a healthy marriage looks like. Ask them how a prenup might contribute to a healthy marriage. Ask them what they think is “fair" and how those views could be reflected in a prenup. When encouraged to explore a prenup as a tool to enhance a healthy marriage, it’s not uncommon for the couple to eventually end up with a fair agreement that satisfies both sides. Most importantly, if done correctly, the process can be viewed as a positive one, and the couple will feel your warmth and love for them shine through.

Avoid the assumption that practicing philanthropy together as a family is a cure-all.

Working closely as a family in pursuit of family values and a shared vision of a better world can be one of the most rewarding aspects of being wealthy. It can also be a train wreck. Families risk frustration and conflict if they assume that because of their altruistic goals, working together on philanthropy must be a positive experience. If you are a controlling, disenfranchising parent, or your kids simply don’t want to work with you in the family business, chances are they are going to feel the same way even if the goals are to make the world a better place – unless you change your approach.

In one such example, the patriarch of a fractured family established a large foundation in hopes of drawing his family back in. The prospect of social impact was enough of a lure to get his family back to the table. His overpowering nature and his uncanny ability to make his adult children feel like incapable youngsters quickly reemerged, however, and poisoned the first grant-making meeting. Storming out of the room, his daughter exclaimed, “Why should I waste my time suggesting grants? You’ll clearly end up judging what I suggest and going with your own opinions.” The “family” foundation was left searching for outside trustees.

To avoid the heartache, or at least the lost opportunities, families need a realistic understanding of their strengths and weaknesses in working together, and they need to be intentional about how to approach giving.

In “Giving Together: A Primer on Family Philanthropy,” The Philanthropic Initiative urges families to start by figuring out their goals for practicing philanthropy together, which will help inform the appropriate process and decision-making approach. Is the purpose of giving together to enjoy working together? Create intergenerational common ground? Build the leadership skills of the rising generation? Foster the growth of a family with disparate interests?

Once a process and guiding principles are established, heeding time-tested best practices may increase the likelihood of a successful outcome. These best practices include identifying and articulating shared values; communicating openly and often, with both sides actively participating; the freedom to come and go as they please; and, perhaps most significantly, a shared focus on social impact.

Avoid buffering your family from your financial representative.

Many of the wealth creators we work with keep the professional representatives they rely on separated from their spouse and children. For some, it’s because they have it under control and there doesn’t seem to be a “need” to engage the rest of the family.

For others, it’s because their family simply doesn’t have an interest in the tax, legal or investment work. Seems logical, right?

However, we also know that it takes years to develop the technical skills needed to effectively communicate and manage professional representatives, and that it can take years to develop a trusting relationship with a financial representative.

This latter point is why we see many family members abandon existing financial representative relationships after the primary relationship-holder is gone. We’re not saying children and spouses should or shouldn’t replace all your financial representatives, but change can be disruptive, and it may open your family to additional risk when you are not there to mitigate it.

And even if your family decides not to replace your financial representatives after you are gone, we know that it takes certain skills to effectively communicate and work with professional financial representatives – especially the sophisticated ones that are needed to navigate the complexity of extreme wealth. If family members are not exposed to professional financial representatives, how can you expect them to be prepared to work with them when the time comes?

In one business-owning family, the patriarch relied heavily on his trusted counsel for all aspects of his family’s life. As his son, who expressed interest in learning more about all aspects of the family business, became more involved, a level of comfort with his dad’s counsel emerged. The youngest daughter, on the other hand, wasn’t engaged in the business and had no interactions with her dad’s financial representatives. When the patriarch passed away suddenly, the siblings were left in two starkly different situations. The brother had comfort and a sense of mutual respect with this cadre of financial representatives. The sister, however, found herself on the defensive. She didn’t know who these old men were, what they did, or how she was expected to work with them, and they picked up on that right away. It was clear to the financial representatives that she was not someone who knew what she was doing, nor did she need to be consulted in the same way as her brother. She felt dismissed as a result, and it took her years of hard work to learn how to advocate for herself and earn the financial representatives’ respect. That is not what the father had wanted for her.

To protect family members from this heartache, take some time to reflect on how your family will need to work with your financial representatives if something should happen to you. Assess the skills they will need to get there, assemble your financial representatives, and co-create a plan.

Be realistic about your family members’ interests and their capabilities, and try to determine if the financial representatives who are right for you will be right for them. Many successful, self-directed investors have realized that their children will never have the investing acumen (or interest) that they do, and have worked to identify a multi-family office solution for when they are gone.

Avoid keeping your estate plan secret from your loved ones.

“Never talk to your family about your estate plan,” one attorney counselled all of his clients. “It causes nothing but headaches.” This unfortunate advice may save that attorney the inconvenience of redrafting a technically perfect estate plan, but it could irrevocably damage family relationships for generations to come.

Talking about estate plans with the people they will affect can be tricky and uncomfortable. It provides transparency into your relationships and exposes how you may feel about family members. Talking about estate plans acknowledges the reality that large sums of money will be dropped into people’s laps, and perhaps more significantly for some, it is an acknowledgment of mortality. Stressful and emotional for sure, it requires a delicate touch. The unintended consequences of not talking can forever change families and legacies. We see two areas of risk that are increased when estate plans are created in secret.

One potential risk is that the estate plan could be created solely around tax efficiencies and not based on the goals and aspirations you have for your family, or on thoughtful consideration of the impact of the wealth (or lack thereof) on future generations, including those not yet born. Again, we are not suggesting that wealth should or shouldn’t be passed down through the generations, or dictating how it should be passed along to various family members. But if the estate plan process begins with the sole goal of pushing as much wealth as far into the future as possible, and is created without any input from the family and other affected players, the plan is less likely to reflect the values, priorities and aspirations of the family. What is the purpose of wealth? To perpetuate for perpetuation’s sake? To enhance lives and realize personal potential? To make the world a better place?

“Might our family be better off returning to shirtsleeves?” asked one patriarch as a way to engage his children in an honest discussion, which ultimately led to a very different vision for his family and the plan for his estate.

The second area where families are at risk of heartache is when the creators of an estate plan assume they know how affected people will interpret and respond to their plan. We worked with a husband who didn’t see the need to tell his wife of 26 years that would she be able to access her money after his death only through a trustee. Is he safe to assume she will appreciate his tax efficiency, or is it possible she’ll feel she was denied control of her money because he did not fully trust her? Might a clarifying conversation before his death be more effective than his posthumous direction?

In another family, a successful hedge fund manager learned years after her mother’s death that her mother had been giving significantly more money to her siblings than to her. While she would have agreed with her mother that her siblings needed the money, while she did not, she was deeply hurt that her mother did it all behind her back. These are feelings she will live with forever, because her mother is no longer alive to work through them with her daughter.

While discussing an estate plan may be hard, it provides a forum for opening up complex issues such as: Whose wealth is it? What is fair among siblings? Is it healthy to give wealth to a grandchild without his or her parents’ permission? Where is the line between enhancing and enabling? How can you predict the impact of wealth on unborn generations?

Opening a dialogue around estate planning also creates an opportunity to talk with your family about the meaning of your wealth: its purpose, your hopes for the impact it can have on the family and your fears for potential harm. Moving beyond a focus on the transfer of assets, these conversations should include the priceless gifts you hope will live on: your memories, your lessons learned and your vision of a life well lived. Guides such as Susan Turnbull’s The Wealth of Your Life: A Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Your Ethical Will can help make these conversations easier.

Avoid resting assured that trusts are always a benefit to the beneficiary.

Jay Hughes, renowned thought leader and practitioner, has been known to say that in the 40 years he’s been informally surveying family trust beneficiaries, roughly 80% say that their trust is more of a negative force in their lives than a positive one. “What? Free money dropped in your lap is bad?” you ask. Many families who have lived through multiple generations of wealth transfer can attest that inheriting a large amount of money can be confusing and disempowering, and can negatively affect the way you feel about yourself – and those negative perceptions of self can easily be multiplied by a well-meaning but misdirected trustee. Dr. Habbershon, in fact, suggests referring to beneficiaries as “impacted persons” to remove the assumption that they will benefit from a trust. “It was so belittling,” said one trust beneficiary, recalling how she had to regularly “slither” into her late father’s attorney’s oak-lined office to make the case for her next distribution. Her trustee was even older than her father would have been, and worlds apart from her. He made it clear that he didn’t understand her life choices and that his job was to protect the money in her trust ... from her. The trustee made her feel that she didn’t deserve the money her father had left her. Was this what her loving father had intended when his attorney encouraged him to reduce taxes by using a trust? The responsibility of avoiding heartache around trusts falls on the trust creator’s effectiveness in preparing both the beneficiaries and the trustees.

To set the beneficiary up for success, trust creators can tell them why a trust will be established, and explain their rights and obligations as a beneficiary, so they don’t feel they are operating from a place of confusion and weakness. More importantly, however, the trust creator can explain the intent of the gift in a way that will allow both parties to reach a mutual understanding of how the money should and shouldn’t be used. In many cases, this decision can release a beneficiary from the emotional baggage associated with receiving “unearned” wealth, and can release the trust creator from feeling the need to “control from the grave” with an overly prescriptive trust.

Additionally, a discussion of the intent of the trust allows the trust creator to explain what is at the root of the trust: love. This place of love from which a trust comes defines the trust as a “gift,” with the aspiration of enhancing a life, rather than as a detached “transfer” for tax efficiency. Hughes, Massenzio, and Whitaker lay out the difference in their Cycle of the Gift: Family Wealth and Wisdom, a must-read on the subject of wealth transfer.

To set the trustee up for success, the trust creator must make sure that the trustee understands what the trust creator wants and doesn’t want for the beneficiaries. A simple conversation today can help a trustee make the best decisions down the road. Better yet, many trust creators have captured this context in writing outside of the legal trust documents, and ask for it to be discussed between the beneficiary and the trustee when they meet for the first time.

As Hughes, Goldstone, and Whitaker point out in Family Trusts: A Guide for Beneficiaries, Trustees, Trust Protectors, and Trust Creators, the initial meeting between a trustee and beneficiary will define the relationship for years. As a trust creator, would you rather have the relationship opened with a stack of legalese slid unwelcomingly across an oak desk to a confused loved one, or with your trustee warmly saying, “I’m here to make sure the trust enhances your life”?

Avoid legislating to lock-in family cohesion through the generations.

Many wealth holders love to daydream about that idyllic, future family reunion that brings together, in peace and harmony, diverse second, third and even fourth cousins, and future stewards of the family name who haven’t yet been born. The family stands hand in hand, singing, surrounded by rainbows and unicorns. In this daydream, by staying united as a family, your progeny have found personal fulfillment, and have multiplied their financial wealth because it has been managed together, rather than having been divided across households.

It’s a great image – and achievable (minus the unicorns). Forcing cohesion, however, through trusts, restrictive financial vehicles or stringent foundation governance, usually leads to a backlash in the long run, even if the moves are well intentioned.

As an example, a serial entrepreneur structured the ownership of his 30 companies to be owned and managed by his four children, although those children had never managed a single business together. After the entrepreneur passed, his children tried to learn this new world, but quickly found they were unable to work together without conflict and strife, which was evident in ultimately abandoning Sunday-night dinners at mom’s – exactly the opposite of the outcome the entrepreneur intended.

Regardless of the structures you put in place, if family members don’t find value in staying together as a family, they’ll at best find ways to separate themselves, or, at worst, kick, scream and litigate to make everyone’s lives miserable until they get out. This is exactly the outcome no wealth holder wants.

Families need to opt into remaining a family. But to opt in, family members need to believe that there is value in staying together. This is the concept of a “family of affinity,” which Dennis Jaffe discusses in Good Fortune: Building a Hundred Year Family Enterprise (another must-read for generational wealth transfer).

Families that bring an opt-in mentality to cohesion continually look for ways to create value as a family and to help family members recognize that value. This value could be emotional support, access to knowledge and experience, understanding the financial benefits of amassed wealth and sustaining an important legacy, giving back to the community from which much was earned or the privilege of bettering the world through philanthropy, to name a few.

To get started, many families leverage fun and educational family meetings to set the tone. One family, upon the sale of the family business, used the proceeds to create both a family foundation and a family travel fund that would encourage trips together. Another, a seven-generation family, has created a stand-alone endowed entity solely to promote family unity through gatherings, education and assistance – an entity that established a family website that identifies hobbies, professional expertise and who is willing to host family members on their couch. Another family went as far as buying an island to entice family members to come together and deepen relationships with one another.

These are examples of the value that comes from deepening relationships, but families that stay together through the generations typically also have beneficial shared financial interests, such as the cost efficiency and investing power of a family office, or shared-impact interests, such as the giving power of a large family foundation.

Family-owned enterprises and the revenue they create can be an effective way to create value, but families need to be sensitive to ownerships or governance policies that may bring about unintended consequences. And in some extreme cases, they may be forced to endure financial setbacks in order to prioritize being a cohesive family. In the example above of the serial entrepreneur’s family, just before the family reached its breaking point, they took a different approach – an opt-in approach. They agreed to put all 30 businesses up for sale, with each sibling deciding whether he or she wanted to buy back any of the businesses, and if so, with whom. When the dust settled, the entrepreneur’s empire was gone, but mom’s dinner table was once again full each Sunday.

Conclusion

Despite our best efforts, heartache is sometimes unavoidable. History is doomed to repeat itself, after all. And while a patriarch or matriarch may be skilled at accumulating wealth over a period of time, his or her affluence does not always lead directly to family happiness in the long term. At Fidelity, we have seen it all: fractured relationships, an overall lack of fulfillment and other negative outcomes resulting from seemingly rational choices, leaving family members disillusioned and with aching hearts.

However, if families knew where to look to recognize some of these hazards, they could alter their approach to avoid heartache in the first place. Sometimes, it’s as simple as knowing where to go to get the right help at the right time. Our hope is that families use this paper as a roadmap to successfully avoid common pitfalls while driving toward their highest goals, be it making a lasting social impact, setting up the next generation of leadership within the enterprise or simply being happy.

Author

Jim Coutré

Vice President, Insights and Connections

Jim Coutré is Vice President, Insights and Connections. He is responsible for the oversight of Fidelity Family Office Services’ Insights and Connections program, which provides families and family office executives with perspective and problem-solving across a wide range of office matters and family matters.